Nuclear Crane Seminar 2019 in Växjö

– Summary

Where Safety and Competence Meet to Lift the Business

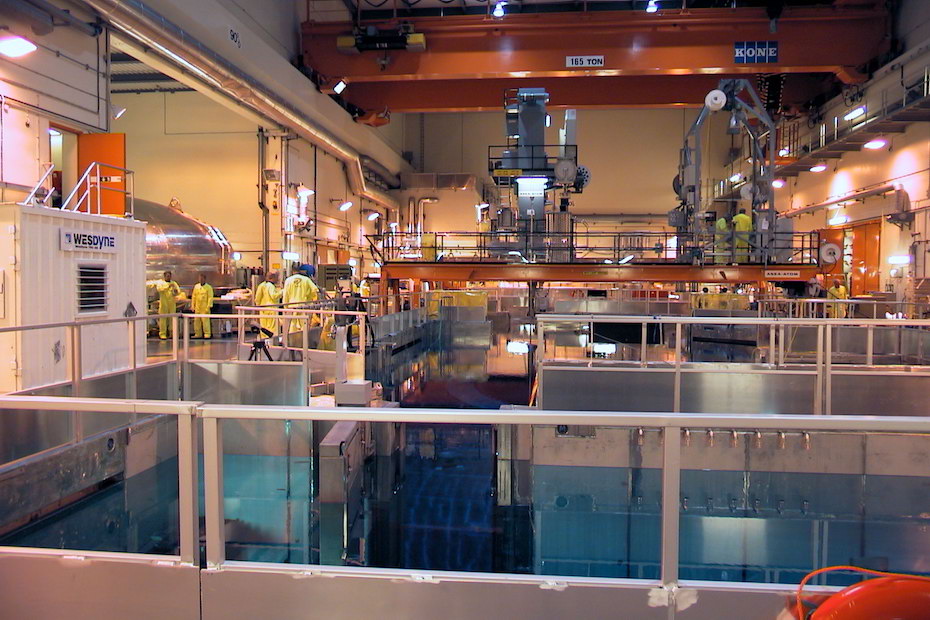

KIKA, the Sweden and Finland based network for crane users in nuclear facilities, successfully organised the third international Nuclear Crane Seminar in Växjö in southern Sweden late May 2019. More than 80 experts on lifting technology and regulations gathered together with users of cranes and other handling equipment in the first green days of the Scandinavian summer. Their objective was to learn more about the fascinating world of cranes in the nuclear world. For all those who could not make their way to Växjö, we have made a short compilation about the subjects of NCS 2019.

From left; Peter Ohlsson, SKB, Reine Bladh, g-ACK, PhD Björn Brickstad, SSM, Dr Hans-Rainer Bath, KTA, Norbert Schilling, NKM Noell, Johan Dagnäs, OKG, Thomas Hagman, RAB, Kjell Andersson, g-ACK and Hannu Rantala, Konecranes.

Eight years have elapsed since NCS 2010 in Växjö, but the same seminar team still keeps rocking the boat. Kjell Andersson, the everlasting dynamo of KIKA, lead the organisers and 3T’s, Thomas Krüger, Thomas Hagman, Tomas Eriksson plus Johan Dagnäs and a lot of Swedish and international friends, supporters and part of the family to turn all the plans and visions for the seminar into reality. And the Swedish summer sun blessed the participants and many happy reunions took place in the Växjö Elite City Hotel, which hosted the venue.

KIKA was formed twenty years ago from the need to create a professional structure in the field of cranes operating in nuclear facilities, since this special area had been left out from the international and national technical and safety standards. Though the focus is very narrow, it is still a very international business. It is an extremely important task to secure the highest possible level of safety and reliability for all lifting equipment in a challenging environment.

Standards and Framework and Special Interviews

Technical standards, regulatory and other institutional framework form a very important section of NCS, leading to interesting discussions among the participants. A corresponding amount of knowledge and expertise in the nuclear crane field might not be found anywhere else in the world.

PhD. Björn Brickstad, former expert at SSM, the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority, brought great news to NCS 2019. The first ever Swedish detailed regulations for lifting equipment in nuclear facilities are on their way – now the old gap left by the machine directive will be filled!

For more information, please read the separate interview with Björn and his colleague Erik Strindö about the progress of the new framework.

Design of cranes may not be the pastime occupation of the majority of us, but some people are devoted to this very important task. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerhard Wagner of the University of Ruhr in Bochum, Germany, is one of those people, whose passion generates safe and reliable technical solutions. At NCS 2019 Prof. Wagner lead the audience into the philosophy of the EN 13001-series standards and all aspects of crane design, from theory to practice.

For more details, see a separate interview made with Prof. Dr.-Ing. Wagner together with Hannu Rantala from Konecranes. As a member in the technical committees CEN/TC 147 and ISO/TC 96 Rantala has a thorough knowledge of crane standards, in particular the EN 15011, the machine directive and the delicate position of cranes in nuclear facilities, somewhere in no man’s land between the common rules. From his unique position he also had the opportunity to compare the provisions of EN standards and the machine directive.

The German KTA (Kerntechnischer Ausschuβ) standards 3902 and 3903 are two of the cornerstones in the safety regulations of all lifting equipment in nuclear facilities and a pattern for regulations in many other countries, for example in Sweden. Norbert Schilling from NKM Noell Cranes in Germany is a dedicated specialist and contributor of the KTA standards and their latest revisions. Read a special interview with him and Dr. H. Rainer Bath about the latest development in the KTA Nuclear Safety standards, for example regarding classification of lifting equipment.

Cranes from Standards to Practice

Theory is a fascinating subject, but in the nuclear crane world safety must be a hands-on subject. In his daily work at g-ACK in Sweden AB Kjell Andersson also encounters both theoretical and practical issues regarding the design of cranes.

“One of the major reasons behind the formation of KIKA in 1999 was the need to bridge the gap between the KTA standards and the documentation used in Sweden. KIKA presented the first draft of a technical specification (TS) in 2006 and in 2011 the second version of the documentation was published.

A central issue of the lecture was evaluation of experiences from different parts of an SFP crane, the backup brake, the support under the hoist drum, the support under the rope sheave and the independent, duplicated rope system.

“One example, according to TBL, the rope anchorage system of the duplicated rope system should be equipped with a damper to secure smooth movement and reduce strain. TBL also requires that load combinations with activation of dampers should be presented.”

During a project in Ringhals 2006 a practical test of the damper was performed under the following presumptions:

Guillotine brake activated on one rope; double load attached to one rope. The theoretical calculated impact factor was given as 1,21 and the measured value was 1,37, which later has influenced the technical specifications of KIKA, now TBL. In EN 13135:2013 is mentioned that a dynamic impact due to failure should be considered, either determined by tests or as a standard value of 1.5.

Lifting Professionals Enhance Safety

As said, NCS is a great forum for crane professionals to meet, users, consultants, technology suppliers and other experts. Two of the presentations focused on equipment and on routines for safe lifting.

The Dutch company Mammoet has a solid background in innovative lifting in demanding conditions. The first nuclear project was accomplished in Swedish Ringhals in 1972. At present Mammoet is busy with decommissioning, upgrading and some newbuilding projects, e.g. Olkiluoto 3 in Finland.

Edvinas Ivanauskas says that the lifespan of a nuclear plant contains many phases, from logistics of new components and fuels to handling during construction, maintenance during shutdowns or turnarounds and finally decommissioning of the equipment.

“Every lifting operation in a nuclear project is different. Lifting of components inside the containment is often extremely demanding and requires a lot of engineering. TLD:s , temporary lifting devices, are commonly used, sometimes in connection with existing lifting equipment to increase capacity. Horizontal positions and small tolerances add challenges to the operations.”

A great example of a working safety culture is provided by AWE, a company formed 70 years ago under the UK Ministry of Defence. The main mission is to develop technology for safe handling of nuclear warheads, including toxic and radioactive materials.

Ian Mitchell says that AWE from the very beginning has supported safety through training, examination, inspection, maintenance and testing.

“Safe lifting results from all these elements. A four-level risk analysis is performed to identify hazards and we will report, correct, prevent and learn from all incidents using a method named “root cause analysis”.

All designs will be subject to tough tests and all systems should be dual, diverse and redundant. AWE aims to use simple, reliable lifting equipment with good margins, example a 3-axis commercial Cartesian robot – costs 1/20 of bespoke and with a long lifespan.

Ian concludes: “Human failings are still the dominant risks. Don’t hesitate to look outside your own plant to identify the world’s leading best practice. Manage people to find the strengths and skills you need, introduce quality control at all stages. Interlocks are never perfect and need maintenance. Understand your own design code.”

The third case in this section about lifting and safety in everyday life is also picked from Great Britain, from the new HPC, Hinkley Point C project, managed by EDF. The reactor building and the fuel building contain a large number of lifting devices, around 15 different designs. In UK an approach to loss of integrity is required, which means that all cranes must be failure free.

James Spencer, Lifting, Handling and Fuel Storage Engineer of the HPC project says that the British argument that any failure is incredible, is extremely difficult and challenging. “In France and in generic EPR design Loss of Integrity is beyond design basis. The internal crane design standards of EDF are classified into three levels based on the FEM code. The fuel handling systems are in their turn based on the German KTA 3902.”

Typical unacceptable causes for loss of integrity are overload, collisions, Hangman’s drop (underload/slack rope detection) and snag/drag cases, for example rope overload that stops horizontal motions.

“Our objective is to demonstrate the absence of ‘cliff-edge’, to identify mitigation measures and to demonstrate feasibility off recovery and above all – to recognise that frequency of LOI is uncertain.”

Lifting in New Projects

With decommissioning on the agenda in many countries it is encouraging to hear about new projects. Fennovoima is a Finnish nuclear power company managing a large NPP project in Pyhäjoki at the coast of Finland.

Vesa-Pekka Arola is the responsible project manager or lifting and transportation equipment at FH-1. He says that most of the lifting and transportation devices are subject to standard government decrees for personal safety, but a number of safety related cranes and other lifting equipment will be monitored by YVL guides, in particular YVL E.11, Hoisting and transfer operations in a nuclear facility.

“Focus during 2019 will be on launching a process of evaluation with STUK, the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority. We are also working on a list of accepted suppliers responsible for the basic design for lifting equipment for the fresh fuel storage, the large polar crane and other devices for the refuelling machine, bridge cranes for the interim storage and other small equipment in zones affected by radioactivity.”

And last but not least, when the fuel has been used to the last feasible kilowatt it has to be stored. In Sweden SKB, the Swedish nuclear fuel and waste management company, runs a long-term research and development project for storage of fuel waste at the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory.

Peter Ohlsson describes the handling of used fuel canisters as a logistic challenge. In the Central Interim storage (CLAB) the fuel has to be received, cooled, cleaned, transferred into casks, the casks has to be, temporarily stored in the underground caverns.

“The fuel elevator is the heart of our plant, but there is a large number of other lifting and handling devices. Each canister has to be handled maybe thirty times. Redundancy and absolute reliability are a must. All nuts are double hanged, the gripper is a fully redundant system, two spindles can take the full loads, the gearboxes are prepared for quick disengagement of either line. The brake system including safety brake is designed for SFP.”

Peter says that some of the cranes are classified according to coming regulations, while other rely on common solutions. The double redundancy system follows KIKA technical specification.

Looking forward into the future

All good things must maybe come to an end, but there is always a future. When Thomas, Tomas and Kjell closed the 2019 NCS seminar and wished the international participants a safe trip back home from Växjö, they already focused on the future. The next NCS seminar is scheduled for 2021/2022, which is a promise for all of us caring about safety in lifting and handling in nuclear plants, which will remain a core subject for the years to come.